It's been a French romantic comedy adapted by an award-winning American playwright, a film and even a Broadway musical, but Tovarich by Robert Sherwood has not received a major production since the early sixties. That is, until now, when, under Bonnie J. Monte's impeccable direction, the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey has mounted an elegant and entertaining production of this play about (very) aristocratic Russian émigrés forced to take domestic jobs with a bourgeois family in 1920s Paris.

Once again STNJ Artistic Director Monte has dusted off a little known play, given it a superb production and enhanced her audience's knowledge of theatrical history. The splendid cast of Tovarich manages, with delicious comic timing and adept performances, to imbue these deluded nobles with a dignity at odds with their down-at-heels situation, while making us care about them very much—so much that, when we learn that a Soviet Commissar who once tortured the Prince and raped the Grand Duchess is a dinner guest they will have to serve, we hold our collective breaths in anticipation of that inauspicious reunion.

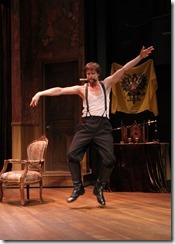

The aristocrats, Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff and his wife Imperial Grand Duchess Tatiana Pêtrovna, are very noble indeed: She is a cousin to the late Czar Nicholas Romanov and he a former general in the Czar's cavalry. And no ordinary soldier, he; one of his jobs was to look out the window and report to the Czar that it was snowing! Having fled to Paris after the revolution—with only his sword, a flag of the imperial guard and a religious icon—the two may have been reduced to living in a hotel attic (and dodging the landlord) and shoplifting food, but they have not lost their "Russian soul." A "true servant of the Czar," the Prince declines to spend even one sou of the four billion francs he has deposited in a French bank because it rightly belongs to the Czar. He awaits the moment when he can return it to Nicholas' real successor, and not a pretender as an former Russian count urges him to do. To survive, the couple finds a domestic position with a French banker's family, and the fun begins. (Above: Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff played by Jon Barker celebrates with a traditional Russian dance.)

The aristocrats, Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff and his wife Imperial Grand Duchess Tatiana Pêtrovna, are very noble indeed: She is a cousin to the late Czar Nicholas Romanov and he a former general in the Czar's cavalry. And no ordinary soldier, he; one of his jobs was to look out the window and report to the Czar that it was snowing! Having fled to Paris after the revolution—with only his sword, a flag of the imperial guard and a religious icon—the two may have been reduced to living in a hotel attic (and dodging the landlord) and shoplifting food, but they have not lost their "Russian soul." A "true servant of the Czar," the Prince declines to spend even one sou of the four billion francs he has deposited in a French bank because it rightly belongs to the Czar. He awaits the moment when he can return it to Nicholas' real successor, and not a pretender as an former Russian count urges him to do. To survive, the couple finds a domestic position with a French banker's family, and the fun begins. (Above: Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff played by Jon Barker celebrates with a traditional Russian dance.)

However, Tovarich is more tragicomedy or dramedy than rollicking farce. We are constantly reminded that the servants are of a higher social status than their employers; they may not know what is expected of servants regarding entering a room and serving, but they are quick studies. Their charm wins over the crusty master and his social-climbing wife, not to mention the their two spoiled children, both of whom set about to learn the Russian language and immerse themselves in the culture by attending émigré parties with Michel and Tina, as the two aristocratic servants are called. Even the nasty Commissar is impressed by their dignity.

Jon Barker as Prince Mikaïl and Carly Street as Grand Duchess Tatiana are appropriately clueless about life, given their privileged backgrounds, but she seems to have adapted better than he, what with her deft fingers at the greengrocer's and her ability to "keep" the accounts—if you could call it that! They are truly fish out of water, too proud to sell their treasures to make ends meet, but imbued with the attitude that "we are born to suffer and to love it." The two actors make the nobles' spunk manifest, so the ending is believable given the characters they have created. The two are no slouches in performing physical comedy: Street has an especially funny bit with the various kinds of kisses Russians give to each other, and Barker's maneuvering around the stage with a sword stuck down his pant leg is priceless. (Above: Jon Barker as Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff pledges his love to his wife, Grand Duchess Tatiana Pêtrovna played by Carly Street.)

Jon Barker as Prince Mikaïl and Carly Street as Grand Duchess Tatiana are appropriately clueless about life, given their privileged backgrounds, but she seems to have adapted better than he, what with her deft fingers at the greengrocer's and her ability to "keep" the accounts—if you could call it that! They are truly fish out of water, too proud to sell their treasures to make ends meet, but imbued with the attitude that "we are born to suffer and to love it." The two actors make the nobles' spunk manifest, so the ending is believable given the characters they have created. The two are no slouches in performing physical comedy: Street has an especially funny bit with the various kinds of kisses Russians give to each other, and Barker's maneuvering around the stage with a sword stuck down his pant leg is priceless. (Above: Jon Barker as Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff pledges his love to his wife, Grand Duchess Tatiana Pêtrovna played by Carly Street.)

As their middle-class masters, Matt Sullivan is a very cantankerous Charles Dupont; he seems to be constantly yelling at someone, but he melts before our eyes when he looks into Tina's soulful eyes. Alison Weller is terrific Fernande Dupont, long-suffering yet easily impressed. Having Russian servants will certainly advance her on the social ladder! Seamus Mulcahy and Rachael Fox play the" rude," "insufferable" (in their parents' words) Dupont children, Georges and Hélène; they morph from monsters into avid Russophiles, a feat brought about by Michel's ability to fence with Georges and Tina's skill at tuning Hélène's guitar and teaching her the song, "Dark Eyes." (Above: Hélène Dupont played by Rachael Fox and Georges Dupont played by Seamus Mulcahy question their new Russian servant, the exiled Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff played by Jon Barker.)

As their middle-class masters, Matt Sullivan is a very cantankerous Charles Dupont; he seems to be constantly yelling at someone, but he melts before our eyes when he looks into Tina's soulful eyes. Alison Weller is terrific Fernande Dupont, long-suffering yet easily impressed. Having Russian servants will certainly advance her on the social ladder! Seamus Mulcahy and Rachael Fox play the" rude," "insufferable" (in their parents' words) Dupont children, Georges and Hélène; they morph from monsters into avid Russophiles, a feat brought about by Michel's ability to fence with Georges and Tina's skill at tuning Hélène's guitar and teaching her the song, "Dark Eyes." (Above: Hélène Dupont played by Rachael Fox and Georges Dupont played by Seamus Mulcahy question their new Russian servant, the exiled Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff played by Jon Barker.)

Less attractive roles are played equally as well. Colin McPhillamy is a pompous Chauffourier-Dubieff, governor of the Bank of France, and Mary Dierson is the haughty Dutchwoman Mme Van Hemert, who causes a revelation that throws the nobles' entire scheme into disarray. But it is Anthony Cochrane as the Soviet Commissar Gorotchenko who nearly steals the show. The final scene, his showdown with the Prince and Grand Duchess drags a bit because it is rather talky as written, but the dramatic tension between the three is electrifying. Despite his despicable past actions, Cochrane's commissar recites from Plato and is respectful toward the former "parasites," complimenting them and, ultimately, turning their efforts to Russia's behalf. We almost like the guy! (Above: Having come face-to-face with Commissar Gorotchenko—an old enemy who needs them—played by Anthony Cochrane, exiles Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff played by Jon Barker and his wife, Grand Duchess Tatiana Pêtrovna played by Carly Street must decide whether to help.)

Less attractive roles are played equally as well. Colin McPhillamy is a pompous Chauffourier-Dubieff, governor of the Bank of France, and Mary Dierson is the haughty Dutchwoman Mme Van Hemert, who causes a revelation that throws the nobles' entire scheme into disarray. But it is Anthony Cochrane as the Soviet Commissar Gorotchenko who nearly steals the show. The final scene, his showdown with the Prince and Grand Duchess drags a bit because it is rather talky as written, but the dramatic tension between the three is electrifying. Despite his despicable past actions, Cochrane's commissar recites from Plato and is respectful toward the former "parasites," complimenting them and, ultimately, turning their efforts to Russia's behalf. We almost like the guy! (Above: Having come face-to-face with Commissar Gorotchenko—an old enemy who needs them—played by Anthony Cochrane, exiles Prince Mikaïl Alexandrovitch Ouratieff played by Jon Barker and his wife, Grand Duchess Tatiana Pêtrovna played by Carly Street must decide whether to help.)

Brittany Vasta has designed a remarkable set, one that is transformed from dingy garret to French drawing room to the below-stairs kitchen, merely by having props carried on and off, draperies "installed" and walls turned round fluidly by the actors and stagehands (attired as befits the play), to the accompaniment of Russian-sounding music designed by Karin Graybash. On opening night, the two scene changes elicited applause. Paul Canada has provided costumes that suit the characters very well; just watching the Prince don his uniform in the final scene is to watch a transformation from servant to master in a few moments. Steven Rosen's atmospheric lighting helps set the scene, and Rick Sordelet's fight direction is, as always, spot-on—and very exciting!

So what, you ask, does a play about Russian emigrés in the mid-1920s say to us today? Well, consider people displaced by subsequent wars or fleeing inhuman conditions—some of them accomplished professionals—who have come to America seeking a "new" life, only to end up driving cabs and working in fast food restaurants. The time and some of the details may be different, but the situation is the same: How does one maintain one's dignity in the face of such soul-rending circumstances? And the overt theatricality of the play mirrors the theatricality of aristocratic life, what with its uniforms, titles and elaborate forms of address.

Tovarich (which means "comrade," a Soviet form of address) shows us the power of hope and pride in oneself and one's culture. As the Prince and Grand Duchess leave the stage, we do not doubt that they will survive, and maybe even thrive, in this "new" world. Some values never change. Thank you, Bonnie Monte, for bringing this play to New Jersey. It's not so musty after all.

Tovarich will be performed at the Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey, 36 Madison Avenue, Madison (on the campus of Drew University), through August 25. For information about performance days and times and for tickets, call the box office at 973.408.5600 or visit www.ShakespeareNJ.org online.

Photos: ©James Morey, The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey

NOTE: The Commissar says he needs money to build tractors for the Russian people. In 1991, I was part of a teacher exchange (Hands Across the Water) that brought NJ teachers to Chelyabinsk, a city in the Ural Mountains 900 miles east of Moscow. During the World War II, the Soviets manufactured tanks there; it was out of the range of the Nazi bombers and, thus, was safe. When I visited, right after Yeltsin swept away the vestiges of the Soviet regime, I visited a traktor zavodska (factory) where they made construction equipment, not tractors!