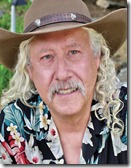

The unruly mane of brown curls is now silver, and Arlo Guthrie, icon of an era, is a member of the Medicare Generation. But judging by his solo concert Saturday night, at Morristown’s Mayo Center for the Performing Arts, he hasn’t lost much to age.

It was a performance that took courage. Guthrie’s wife of 43 years, Jackie, died last month. He spoke briefly of his loss, talking about his first meeting with “the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen” and following up with a ballad, the name of which I unfortunately don’t know.

But not dwelling on the sadness, Arlo was, to put it simply, Arlo. He told stories of his growing up, stories about his father and the other legendary musicians who were everyday visitors to the Guthrie home: Leadbelly, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott and, of course Pete Seeger, with whom Arlo toured for years.

Those of us who remember his unique anti-war anthem, “Alice’s Restaurant,” (no, he didn’t sing it at Mayo) know his prodigious gift for talking. After months of touring with his family (16, including children and grandchildren), he seemed to be enjoying connecting with the large Morristown audience, most of whom appeared to be baby boomers. With his relaxed Southern twang that belies the fact that he grew up in New York City, he has an inimitable gift of gab.

Those of us who remember his unique anti-war anthem, “Alice’s Restaurant,” (no, he didn’t sing it at Mayo) know his prodigious gift for talking. After months of touring with his family (16, including children and grandchildren), he seemed to be enjoying connecting with the large Morristown audience, most of whom appeared to be baby boomers. With his relaxed Southern twang that belies the fact that he grew up in New York City, he has an inimitable gift of gab.

Arlo, accompanying himself on a variety of guitars, all acoustic, including a 12-string, and briefly on a piano, sang lots of his dad’s songs. “Pretty Boy Floyd,” he pointed out, sounds like it could have been written yesterday. The same is true of “Deportees,” which he also sang. The politics that were born in the Dust Bowl have a peculiar resonance now, some 80 years later, in light of our recent presidential campaign. Who said, “The more things change, the more they stay the same?”

Toward the end of the show, he did a monologue about touring all over the world with “This Land is Your Land” and trying to make it relevant to other countries. At one point, he said, he realized that “from California to the New York island” was what it is about. He commented that, a couple of decades back, everyone would have joined in. This is a more buttoned-up age, he suggested. But I beg to differ. Everyone sitting around me knew all the words and seemed to be itching for an invitation to sing along.

Arlo, of course, is a prodigious songwriter in his own right. He didn’t do “Alice,” but he did his silly and delightful “Motorcycle Song” and “Coming Into Los Angeles,” his tribute to the drug culture and/or the war against it. And he sang “City of New Orleans,” which was written by the late Steve Goodman. Arlo sings it better than anyone else.

I don’t know whether Arlo deserves credit for this or not, but this was a rare show with no CDs, t-shirts or posters on sale in the lobby. There were, however, buckets for contributions to the American Red Cross for Hurricane Sandy relief. Arlo was clear that he had nothing to do with that effort, but he mentioned it from the stage and encouraged the audience to help.

There was a lot of nostalgia in the show, but also a lot of tying together of the past and the present. Woody Guthrie’s legacy, now his son’s legacy, of championing social justice and the rights of the common man, never gets old.