In my high school English classes, I often asked my students to think of literature as both a window and a mirror: a mirror that reflects the universal human experiences we all share (love, death, friendship, betrayal, to name a few) and a window look through which we can learn about cultures and experiences we may know nothing about.

In my high school English classes, I often asked my students to think of literature as both a window and a mirror: a mirror that reflects the universal human experiences we all share (love, death, friendship, betrayal, to name a few) and a window look through which we can learn about cultures and experiences we may know nothing about.

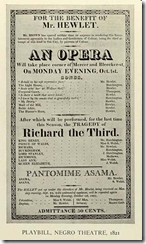

This adage was brought home to me at the opening night performance of Carlyle Brown's 1987 play, The African Company Presents Richard III, The Theater Project's current production at Union County College in Cranford, where it will run through May 15. I knew nothing about such a theater company active in Manhattan in the 1820s, formed by a group of free and runaway slaves (several from cane plantations in the West Indies), nor had I ever thought about the myriad roles slaves had to play throughout their lives. This play opened my eyes and made me want to learn more this forgotten moment in the cultural life of the times. After all, Denzel Washington was not the first black actor to portray Richard III (in 1990 at the NY Shakespeare Festival)!

Set 50 years after independence and 40 years before the Civil War, the play—inspired by a true story—describes the obstacles encountered by a troupe of African American actors as they attempt to produce and perform Shakespeare's Richard III in Manhattan. Because their theater just happens to be located next door to the Park Theatre, newly reopened after a fire and featuring the great British actor Junius Brutus Booth in the title role of the same play, the white theater manager enlists the police to close down the African American production, thus neatly disposing of what he considers to be a "travesty" and potential competition. Behind the scenes, during rehearsals, the company members struggle with having to portray characters and recite dialogue they dislike, their own painful histories, the hypocrisy of their social identities and their yearning for a theater that reflects their own desires and goals. In a jail cell, however, after they've agreed not to produce any more Shakespearean plays, company manager Billy Brown produces a script he's written based on the 1796 uprising of black slaves against the English navy and thought to be the first work by an African-American playwright to be performed in the United States, thus bringing the promise of renewal and hope to the group.

Set 50 years after independence and 40 years before the Civil War, the play—inspired by a true story—describes the obstacles encountered by a troupe of African American actors as they attempt to produce and perform Shakespeare's Richard III in Manhattan. Because their theater just happens to be located next door to the Park Theatre, newly reopened after a fire and featuring the great British actor Junius Brutus Booth in the title role of the same play, the white theater manager enlists the police to close down the African American production, thus neatly disposing of what he considers to be a "travesty" and potential competition. Behind the scenes, during rehearsals, the company members struggle with having to portray characters and recite dialogue they dislike, their own painful histories, the hypocrisy of their social identities and their yearning for a theater that reflects their own desires and goals. In a jail cell, however, after they've agreed not to produce any more Shakespearean plays, company manager Billy Brown produces a script he's written based on the 1796 uprising of black slaves against the English navy and thought to be the first work by an African-American playwright to be performed in the United States, thus bringing the promise of renewal and hope to the group.

Mark Spina gamely tries to get a steady hand on the production, but the play as written is a bit unruly and uneven. The riveting story line is almost derailed by the playwright's inclusion of a gratuitous and unconvincing love story between Ann and Jimmy Hewitt, the two "stars" of the company. When Ann suddenly disappears, production grinds to a halt, only to restart when Hewitt quickly requites her love in time for the show to go on. Too, some of the speeches sound more like sermons than conversation, and the discriminatory white characters are stereotypical villains who gnash their teeth at the thought of African Americans daring to "play" Shakespeare.

These unthankful roles were performed very well by Gary Glor as theater impresario Stephen Price and David Neal as the Constable Man. Glor visibly seethes and trembles at the very thought of a rival—horrors: African American!—company putting on Richard III next door to his theater. "Tonight the curtain falls on Mr. Brown's sable little pageant," he says with wicked relish. And Neal's constable gets in on the act, reciting Hamlet's "to be, or not to be" soliloquy with a mouth full of apple! One gets the impression that he has little stomach for shutting down the African Company, but once Price appeals to his sense of duty, he has little choice but to prevent the anticipated "civil discord."

These unthankful roles were performed very well by Gary Glor as theater impresario Stephen Price and David Neal as the Constable Man. Glor visibly seethes and trembles at the very thought of a rival—horrors: African American!—company putting on Richard III next door to his theater. "Tonight the curtain falls on Mr. Brown's sable little pageant," he says with wicked relish. And Neal's constable gets in on the act, reciting Hamlet's "to be, or not to be" soliloquy with a mouth full of apple! One gets the impression that he has little stomach for shutting down the African Company, but once Price appeals to his sense of duty, he has little choice but to prevent the anticipated "civil discord."

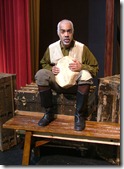

The members of the African Company, were rather more believable. Daaimah Talley, as Sara, has two affecting speeches about her relationship with her employer Mrs. Van Dam; her performance in the play enables the white woman to recognize her servant as a human being. Likewise, Bliss Griffin (left, with Michael Flood as Jimmy Hewlett) endows Ann with an attractive feistiness as she balks at having to play Lady Anne, seduced over her father's coffin by the wicked Richard!

The members of the African Company, were rather more believable. Daaimah Talley, as Sara, has two affecting speeches about her relationship with her employer Mrs. Van Dam; her performance in the play enables the white woman to recognize her servant as a human being. Likewise, Bliss Griffin (left, with Michael Flood as Jimmy Hewlett) endows Ann with an attractive feistiness as she balks at having to play Lady Anne, seduced over her father's coffin by the wicked Richard!

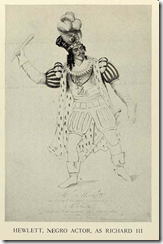

It takes the rather arrogant Jimmy Hewlett, played assuredly by Michael Flood, to remind her of the varied roles played by slaves all the time (maids, mothers to children not theirs, menservants). Indeed this character voices the benefits of African Americans' appearing onstage. In a monologue, he intones, "I get to be loved and accepted. To be openly admired. To feel myself, to be full of myself. To breathe air and give it back again. To make myself as if I were clay.... The makeup, the costumes, and the robe. It's all glass that I know how to polish and make clear. So that any man can see that I am any man." That former slaves can portray kings and queens sure is heady stuff.

It takes the rather arrogant Jimmy Hewlett, played assuredly by Michael Flood, to remind her of the varied roles played by slaves all the time (maids, mothers to children not theirs, menservants). Indeed this character voices the benefits of African Americans' appearing onstage. In a monologue, he intones, "I get to be loved and accepted. To be openly admired. To feel myself, to be full of myself. To breathe air and give it back again. To make myself as if I were clay.... The makeup, the costumes, and the robe. It's all glass that I know how to polish and make clear. So that any man can see that I am any man." That former slaves can portray kings and queens sure is heady stuff.

As the troupe's conscience, Papa Shakespeare, Lorenzo Scott (left) portrays a resilient Caribbean griot with soft authority, despite the fact that he was probably named Shakespeare by a master who thought it was a good joke to give a slave such a name. Laurence Stepney (above, right) gives the company's founder and leader, Billy Brown, the dignity and presence needed to even think of mounting such a production!

As the troupe's conscience, Papa Shakespeare, Lorenzo Scott (left) portrays a resilient Caribbean griot with soft authority, despite the fact that he was probably named Shakespeare by a master who thought it was a good joke to give a slave such a name. Laurence Stepney (above, right) gives the company's founder and leader, Billy Brown, the dignity and presence needed to even think of mounting such a production!

Thomas Rowe has designed a multipurpose set based around a proscenium arch, as if to remind us of the theatrical nature of the goings on; a couple of trunks, a bench and a basket are all we need to transport us back in time and place. Eleni Delopoulous's costumes are appropriate yet unobtrusive; the men’s clothing was especially snappy. And Michael Magnifico's sound design—comprised of African chants, Negro spirituals, slave melodies and music from the era ("I Dream of Jeannie" most prominently)—really sets the scene for the audience and actors.

Unevenly written, The African Company Presents Richard III is, nevertheless, professionally performed, and although Zoya Bromberg's program notes are informative, I found myself hungry to find out more about what happened to this revolutionary troupe of actors. History lesson, sociology project, a treatise on the nature of dramatic performance, The African Company Presents Richard III is a worthy addition to the local theater scene.

The African Company Presents Richard III will be performed Thursdays through Saturdays at 8 PM and Sundays at 3 PM at Union County College, 1033 Springfield Avenue, Cranford. For tickets and information, call 908.659.5189 or visit online at www.thetheaterproject.org.

If you decide to take a teenager to see the play (recommended), here is a study guide you can download.