Developed over the past four years in various workshops across three continents as South Africa prepared to host last summer’s World Cup competition—which occurred amid great fanfare and tooting of vuvuzelas—Train to 2010 examines the effect of change on the haves and have-nots in, this case, the native citizens of post-apartheid South Africa. Mamba uses a metaphorical runaway train hurtling down unfinished tracks way below ground to highlight the tensions between black South African citizens who came of age after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison and election as president in 1994 and those who participated in and survived the anti-apartheid movement that wracked the country in the late sixties and seventies.

The plot is simple and straightforward: as two men, young apprentice engineer Sifiso and his older helper, the laborer Vavi work the night shift underground, drilling in preparation for the laying of train tracks, an accident occurs, knocking both men unconscious. As a train appears to roll in (we never really see it, but an older conductor and his younger apprentice appear to direct the action), Sifiso and Vavi (left) regain consciousness and board the train. The younger, more educated man enters First Class, where he eats, smokes cigars and drinks fine whiskey while conversing with two entrepreneurs about his idea of a high-speed train line that will hot only connect Johannesburg and Cape Town but all of Africa. Meanwhile, Vavi finds himself in Ordinary Class accommodations, where there is no food, nothing to drink and it is bitingly cold. So much for the change Sifiso touts in the opening scene; Vavi, and we, realize that “when things change, they do not change for everyone the same.” (Photos: Sherry Rubel)

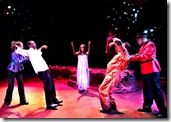

The plot is simple and straightforward: as two men, young apprentice engineer Sifiso and his older helper, the laborer Vavi work the night shift underground, drilling in preparation for the laying of train tracks, an accident occurs, knocking both men unconscious. As a train appears to roll in (we never really see it, but an older conductor and his younger apprentice appear to direct the action), Sifiso and Vavi (left) regain consciousness and board the train. The younger, more educated man enters First Class, where he eats, smokes cigars and drinks fine whiskey while conversing with two entrepreneurs about his idea of a high-speed train line that will hot only connect Johannesburg and Cape Town but all of Africa. Meanwhile, Vavi finds himself in Ordinary Class accommodations, where there is no food, nothing to drink and it is bitingly cold. So much for the change Sifiso touts in the opening scene; Vavi, and we, realize that “when things change, they do not change for everyone the same.” (Photos: Sherry Rubel) As the main plot unwinds, playwright Mambo provides us (and his two protagonists/antagonists) with glimpses of the past, a time both would rather forget. Their parents held jobs typical to native South Africans—domestic worker, gold miner (and would-be revolutionary)—setting the stage for their sons’ accomplishments. Vavi joined the anti-apartheid movement, becoming “the coolest cat with a petrol bomb,” and Sifiso matriculated at an all-white school and went on to MIT. The former would like to forget his past; the latter (inspired by the success of Barack Obama) intends to use his to get ahead, to “become anything [he dreams].” Complicating matters is an even more distant past: that of the native ancestors. Told that a power station he proposes for his railway scheme will destroy an ancient burial ground, Sifiso blithely disregards the concern, calling the people living there “squatters” whom he will have moved off the land. To underscore the disconnect between these two generations of black South Africans, Sifiso and Vavi, Mambo has the former say, “These people [in First class] are me,” to which Vavi replies, “You don’t see [those of us less well-off], therefore they do not exist.”

As the main plot unwinds, playwright Mambo provides us (and his two protagonists/antagonists) with glimpses of the past, a time both would rather forget. Their parents held jobs typical to native South Africans—domestic worker, gold miner (and would-be revolutionary)—setting the stage for their sons’ accomplishments. Vavi joined the anti-apartheid movement, becoming “the coolest cat with a petrol bomb,” and Sifiso matriculated at an all-white school and went on to MIT. The former would like to forget his past; the latter (inspired by the success of Barack Obama) intends to use his to get ahead, to “become anything [he dreams].” Complicating matters is an even more distant past: that of the native ancestors. Told that a power station he proposes for his railway scheme will destroy an ancient burial ground, Sifiso blithely disregards the concern, calling the people living there “squatters” whom he will have moved off the land. To underscore the disconnect between these two generations of black South Africans, Sifiso and Vavi, Mambo has the former say, “These people [in First class] are me,” to which Vavi replies, “You don’t see [those of us less well-off], therefore they do not exist.” Using masks, dance (sinuously choreographed by Dianne Mcintyre) and native music (sound design by Alec LaBau), playwright Mamba and director Ricardo Khan have woven an intricate tapestry of post-1948 South Africa, complete with chilling details of demeaning treatment, torture, edicts that even affected the language native children would learn in school (Afrikaans, the tongue of the oppressor, which they resisted and for which they were shot), and the hopes of black citizens and the rest of the world that soared with Mandela’s release from Robbin Island prison and the long lines of people waiting peacefully, often for days, to vote him into the presidency in 1994.

David Hawkinson, Tabitha Pease and John Ezell have designed a beautiful set that suggests the dank underground chamber where the men work and contrasts it with South Africa’s natural beauty through two huge stained-glass flower-like installations that frame the stage. Various props define other locations, from the First Class and Ordinary Class cars to a white woman’s dining room and Vavi’s native home. Costumes by Suzanne Mann and lighting by Victor En Yu Tan enhance the setting and the action, visually and atmospherically.

However, it is the actors who drill this riveting story into our suburban American consciousness. The two leads, Yusef Miller (Sifiso) and Sibusiso Mamba (Vavi) are outstanding—sympathetic and irritating at the same time. Miller conveys the optimism of a young man accorded many educational opportunities unavailable to natives 30 years prior. With his head high (his nose in the air) and a twinkle in his eye, he convinces us that he will be a part of South Africa’s “dropping feet first into the 21st century.” Mambo’s Vavi is the personification of defeat, a man who will never ride first class in any train, let alone one going to the World Cup; indeed, he will never even attend the World Cup. He wants to build a new train (i.e., nation of South Africa) without a First or Ordinary class, a suggestion that leads Sifiso to re-think his plan for the power station.

However, it is the actors who drill this riveting story into our suburban American consciousness. The two leads, Yusef Miller (Sifiso) and Sibusiso Mamba (Vavi) are outstanding—sympathetic and irritating at the same time. Miller conveys the optimism of a young man accorded many educational opportunities unavailable to natives 30 years prior. With his head high (his nose in the air) and a twinkle in his eye, he convinces us that he will be a part of South Africa’s “dropping feet first into the 21st century.” Mambo’s Vavi is the personification of defeat, a man who will never ride first class in any train, let alone one going to the World Cup; indeed, he will never even attend the World Cup. He wants to build a new train (i.e., nation of South Africa) without a First or Ordinary class, a suggestion that leads Sifiso to re-think his plan for the power station. Able supporting actors include Caroline Gombe as Vavi’s mother Eunice and Alvin Keith as his father Amos; Juliette Jeffers as Sifiso’s mother Paulina and Heddy Lahman as her employer Erica (and later as fierce white revolutionary Melissa); Adam Ludwig and Edward O’Biennis as the white and black railroad entrepreneurs, respectively; Kila Packett as Melissa’s husband and co-revolutionary; and David Ryan Smith as the older imperious, officious conductor, intent on getting the train to its destination, and Zoey Martinson as his younger, more compassionate apprentice.

If you saw the film Invictus and came away suffused with good vibes about democracy in South Africa, Train to 2010 will make you re-think those rosy assumptions. While the democratically elected government has changed (literally, color-wise), are things on the ground (like poverty, educational and job opportunities, medical attention, housing) any different, save for the fact that the police can’t break into houses and arrest people for no other reason than the color of their skin? Rest assured, however, that South Africa will continue its trek into the future, for as Sifiso rightly notes, “If the train stops, people will say that black people took over and accomplished nothing.” And that would be a tragedy.

Train to 2010 will be performed at the Crossroads Theatre, 7 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, through October 24. Performances are Thursday through Saturday, October 21-23, at 8 PM and October 17, 23 and 24 at 3 PM. Tickets can be purchased by calling the box office at 732.545.8100 or online at www.CrossroadsTheatreCompany.org.